The Kuffners

The Kuffners - The History and the Key Personalities

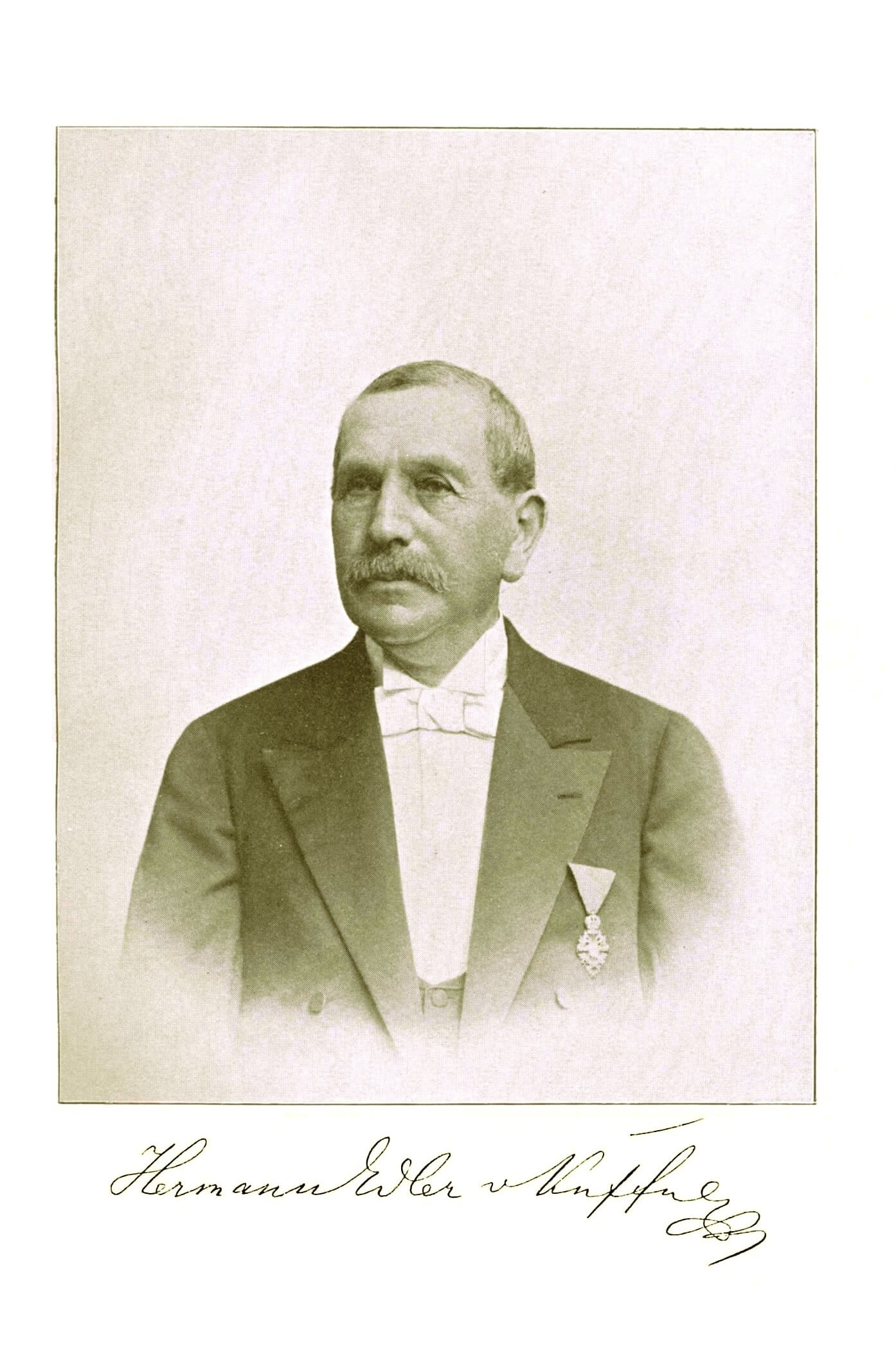

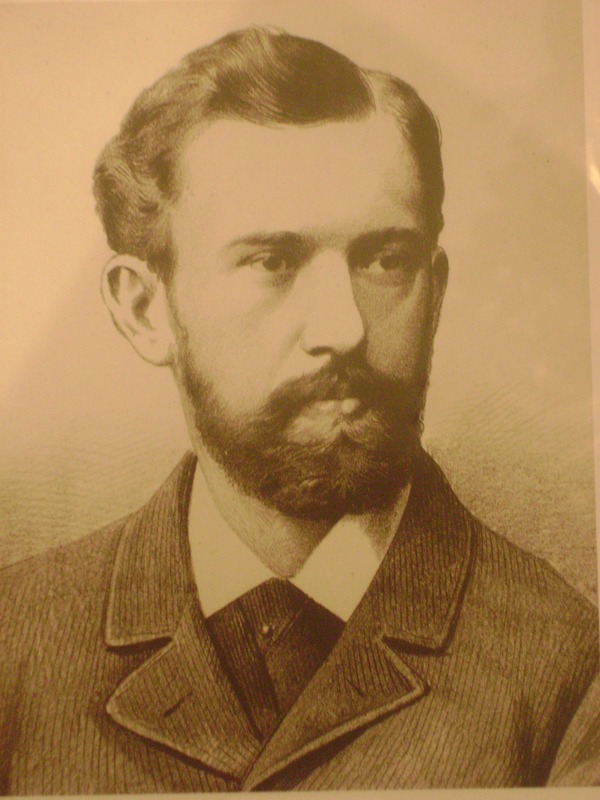

From the 16th century until October 1938, those shaping the history of our town included Jewish citizens; among these, the town of Břeclav (Lundenburg in German) was the cradle of an important Jewish family – the Kuffners. Gradually, the family made an indelible mark on the faces of the towns and cities of Břeclav, Vienna and Sládkovičovo. Kuffners were active in the sugar and brewing industries as well as in farming. They became officials of Jewish communities and mayors, established foundations and dedicated efforts to social and humanitarian issues. Extensive building activities and valuable art collections were left behind by the family. All these merits were the reason the Kuffners were elevated to the status of nobility at the turn of the 20th century. From the beginning of the 19th century, sugar beet was one of the most widely used agricultural raw materials in the Czech Lands; almost every major town had its own sugar factory through the years. In terms of total production, however, few were able to match the increasingly dynamic sugar empire of the Kuffners, who were one of the original Familianten families in Břeclav (i.e. those that were officially allowed to reside in the town). They masterfully took advantage of the economic and social emancipation of the Jewish population in the first half of the 19th century; within the next few decades, they were already one of the most important Jewish families of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Juda Löbl – the son of Samuel from Bučovice – who died one Sabbath night in 1731, can be considered to be the first known ancestor of the family. We know that in 1720 he rented the local princely distillery and founded the family business tradition. He was otherwise a great chess player and Prince Josef Václav of Liechtenstein had a house (No. 98) built for him in Břeclav near the bridge of Mariánský most, in gratitude for a game the Prince won with a French marquis in 1723. The house was retained in the family assets until 1938 and was destroyed during the Allies’ air raid in November 1944. In 1787, when a patent was issued for the adoption of a new name and surname for Jewish residents (Jews had to adopt a permanent German surname and choose a personal name from a list of 109 permitted male and 35 female names), the family adopted the name of Kuffner. The princely distillery was then successfully passed on to descendants, who gradually added the wool trade, supplying the Austrian army during the Napoleonic Wars, establishing weekly grain markets in Břeclav, and making liqueurs and rosolio. Included was also the construction of a malt house and the lease of the Lichtenstein brewery. The large concentration of family wealth also significantly benefitted from the profitable and rich dowry-bringing marriages. Throughout the 19th century, various Kuffner family lines were unprecedentedly united, and the high number of marriages between first-level cousins was also striking. The Kuffners’ ever-increasing social status within the Monarchy is also evidenced by their marriage connections with major Jewish entrepreneur families – the Hamburgers and Ehrenstams of Prostějov, the Iritzers and Holitzers of Vienna, and the sugar dynasties of the Strakoschs and the Redlichs. In 1849, as a result of revolution events, the Familiant Law was abolished and the free movement of the Jewish population was made possible. Some members of the Kuffner family, Ignaz and his cousin Jacob, took advantage of this situation and moved with their families to the outskirts of Vienna, where they bought breweries. In the capital of the Austrian monarchy, they form the two main family’s Vienna lines. With the purchase of land and the building of a sugar factory in the then Upper Hungarian town of Dioszegh (today’s Sládkovičovo, Slovakia) in 1867, the Slovak family line was established, represented by Karl Kuffner (Jacob’s younger son) and his family. The original Břeclav family branch reached its economic and social peak in the person of Hermann Kuffner, the main builder of the sugar factory complex (1862) and the extensive farmsteads. This main Kuffner branch died out with the childless Ludwig Kuffner in 1937, and the female line continued in Canada. Both the Austrian and Slovakian lines were forced to leave their place in 1938–1939, and some of their family members found their last place of rest in the Nazi extermination camps. The descendants of the survivors found their new homes primarily in the United States. Traces of Kuffners’ activities can still be seen in Břeclav (sugar factory complex, tenement houses, synagogue or Jewish ceremonial hall), in Vienna (Ottakringer brewery, townhouses, observatory) and Sládkovičovo (manor house, park with mausoleum, sugar factory and adjacent buildings).

The Kuffners - The Industrial and Architectural Heritage

The Břeclav Synagogue

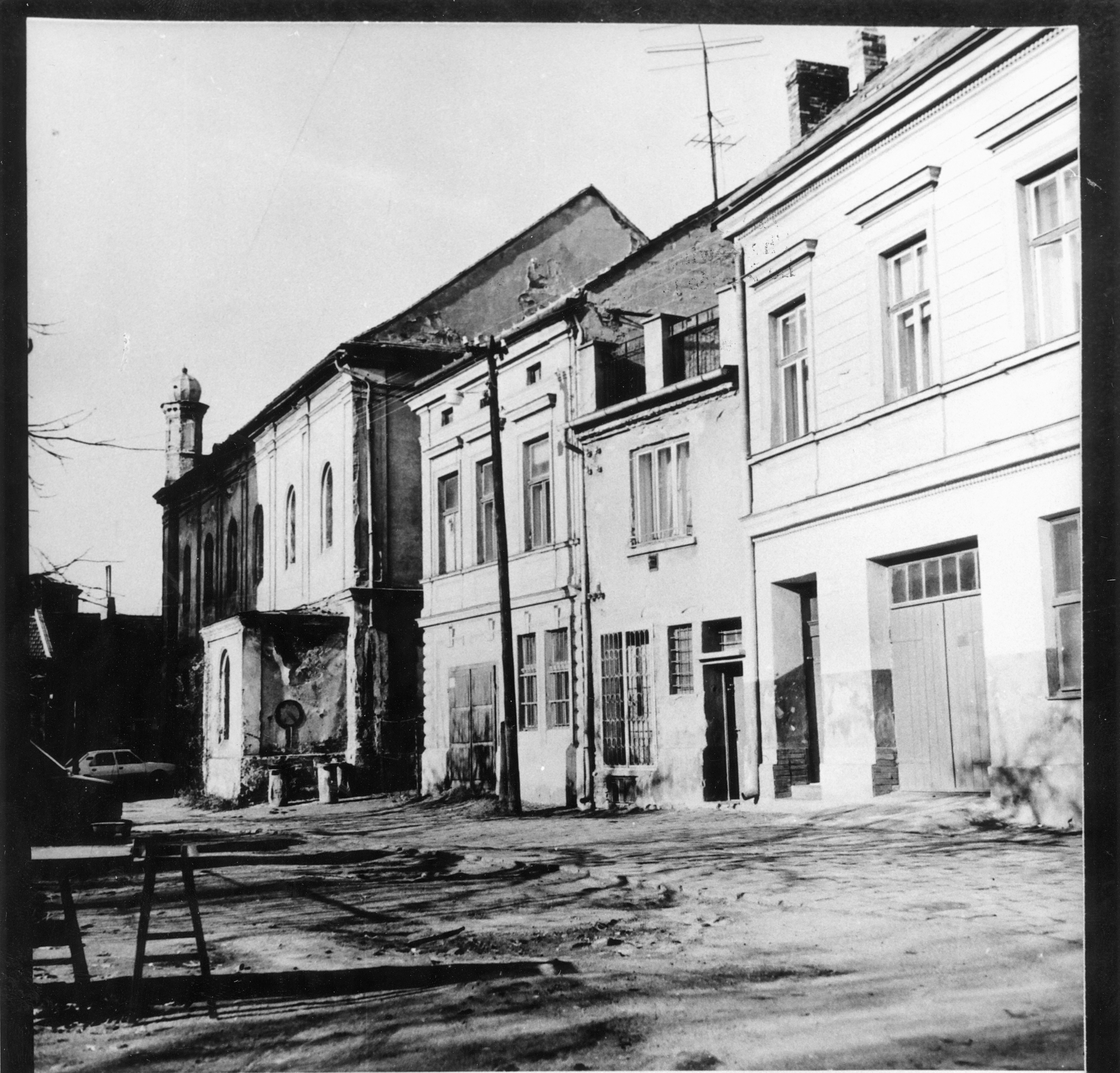

The synagogue in Břeclav in its present form is the result of the last construction project in 1868, when the existing building, already insufficient in space, was taken down. The chief official of the Jewish community of Břeclav David Kuffner, father of the future mayor of Břeclav, Hermann H. Kuffner, was the contracting and financing authority of the construction project. Twenty years later, as the mayor, Hermann H. Kuffner signed the contract for the finishing touches to the building and especially the interior decoration with the prominent architect Max Fleischer (1841–1905), a Jewish native of Prostějov. After its renovation in 1888, the synagogue became one of the most presentable ones. It retained the traditional separate main space for men and the space referred to as the women’s gallery on the first floor, which was also accessed by separate entrances. In total, it contained 417 seats; the presence of an organ located in this very space was a rarity. From the second half of the 19th century, the Jewish community of Břeclav was a Reform community, therefore instrumental music was possible in the services. Thanks to Rabbi Dr. Jindřich Schwenger (rabbi in Břeclav in 1911–1931) the liturgy also used the Czech language. The property attracts attention above all by the combination of the external Neo-Romanesque style and the interior decoration in the Moorish-Oriental style. The architect based his design on the then fashionable, though eclectic, style of historicism. The dominant feature of the northwest façade is a massive gable with a central circular motif, topped by a stone Decalogue with two turrets on the edges. The Hebrew inscription above the main entrance was restored (“Enter His gates with thanksgiving, His halls with praise” – Psalm 100:4, Old Testament). The interior of the hall is illuminated by massive decorative chandeliers. The electrification of the synagogue took place around 1930. The Břeclav Jewish community was allowed to use the synagogue for its religious purposes only until the beginning of October 1938. After the occupation of the town by the German army, the last Jewish inhabitants were interned on the border with the so-called Second Republic and only in November of the same year were they transferred to the assembly camp in Ivančice. The interior of the synagogue was looted during the Nazi occupation, probably in the spring of 1942. After 1945, the Jewish community was not restored in Břeclav and the synagogue gradually served as a storage area (furniture, dry goods and vegetables) for many decades. The building was renovated in 1997–1999 after the town of Břeclav took over the building from the Brno Jewish community for a symbolic sum, with the proviso that the town would restore the synagogue and use it for cultural and social events. Since 2000 the building has been managed by the Municipal Museum and Gallery of Břeclav and since 2009 a permanent exhibition dedicated to the history of Břeclav Jewry has been available in the women’s gallery.

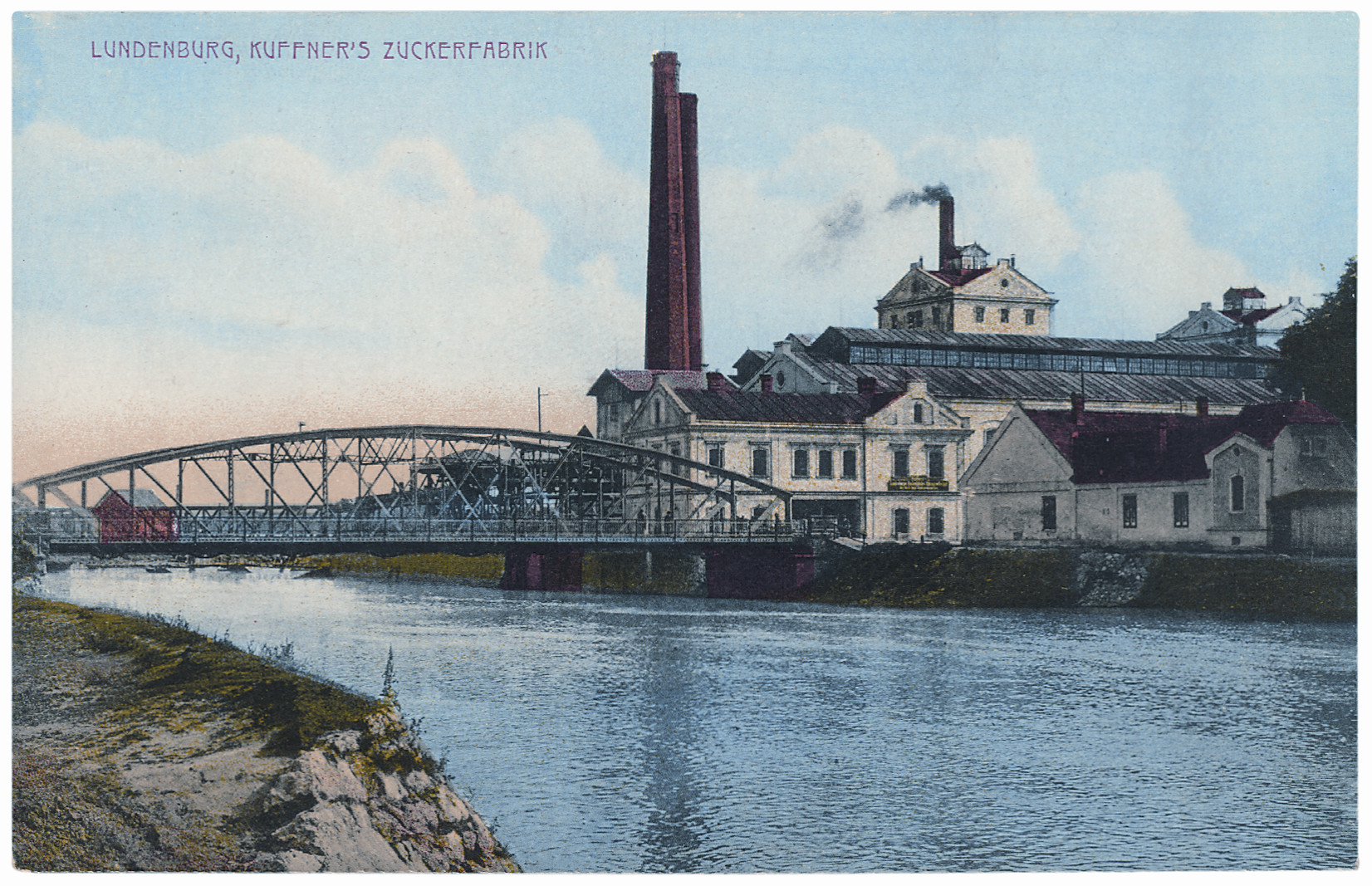

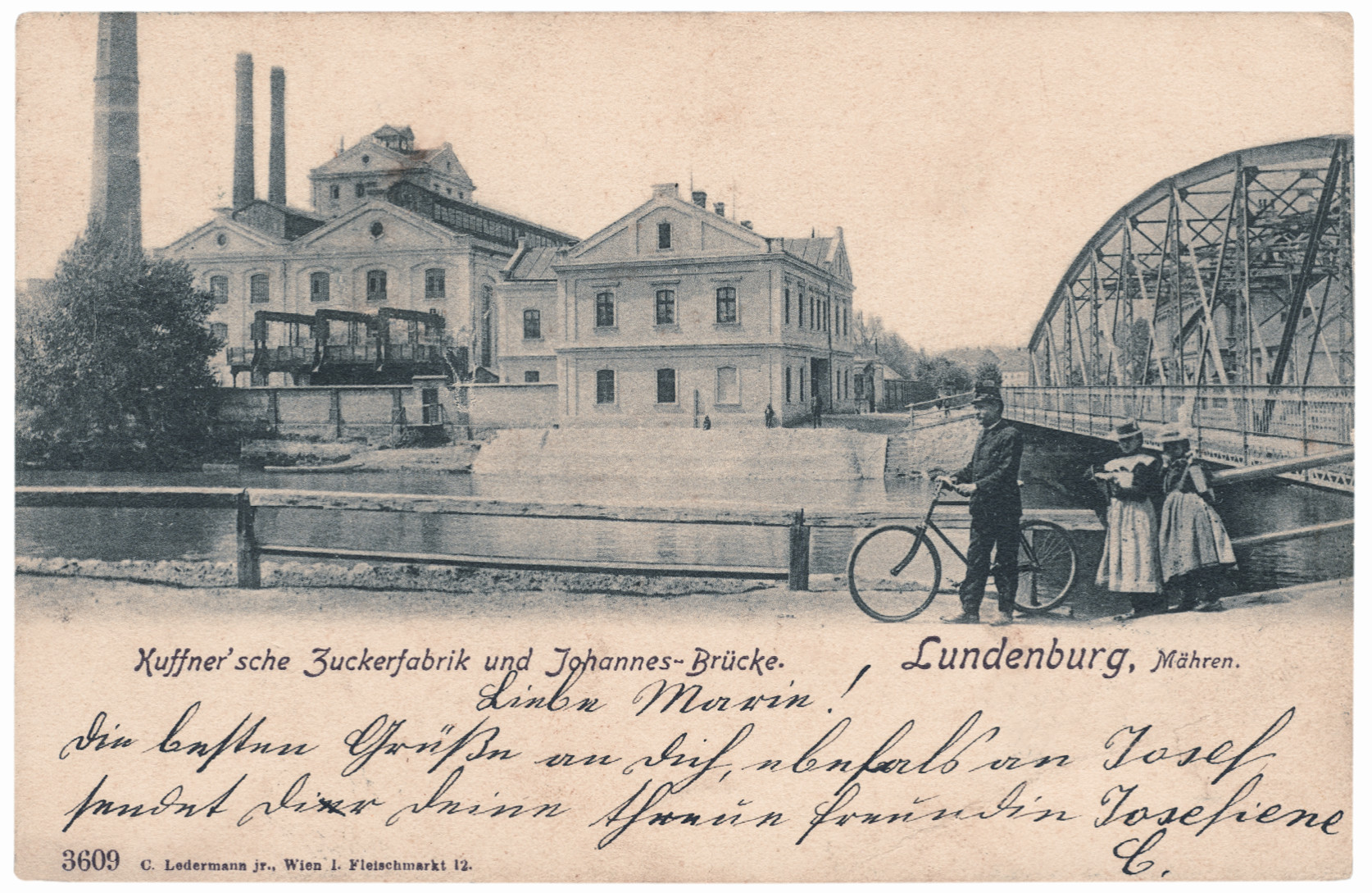

Kuffner Sugar Factory in Břeclav

The Kuffner family (brothers Hermann, Jacob and cousin Ignaz) established the sugar factory in 1861 and launched its operation in 1862. In particular, the operation of Kaiser Ferdinand’s Northern Railway provided favourable conditions for the newly developing food industry – in the form of excellent communication services and also sufficient land available for growing sugar beet. Kuffner’s sugar factory was built as a mixed factory, i.e. it produced white sugar from beet and thus had both a raw sugar factory (a plant where the beet is processed into raw sugar) and a refinery (a plant where the raw sugar is purified into white – refined sugar. The sugar refinery operated under the company called Kuffnerův břeclavský cukrovar (Kuffner’s Břeclav Sugar Refinery) initially processed 1500 q of beet per day. The raw sugar obtained was refined and made into sugar loaves. In addition to the sugar factory, the Kuffners also established a distillery and a yeast factory, which operated until 1892. From 1880 they also operated a malt house. The rapid growth of the family business was also made possible by the generous expansion of the land holdings by renting land and farmsteads from Prince Liechtenstein. The purchase of the former peasant shareholder sugar factory in Podivín in 1890, where all the sugar beet was processed, also proved to be a profitable business move in 1893, when the Břeclav sugar factory burnt to the ground. Construction of new buildings began that same year, and by the following sugar season the upgraded factory with modern machines was processing 8,000 q of beet daily and the daily production of white goods reached 1,000 q of loaves, cubes and loose sugar. As the operation of the sugar factory continued to be improved, by the time of the coup d’état the daily production included 12,000 q of processed beet. However, the Kuffners also successfully carried out additional economic activities on their numerous farms and plots of land – they grew high-quality malting barley, but apart from sugar beet, their biggest yields came from the then very modern cattle and pig farming. The noble breeds of Dutch cows in particular provided high milk yields, and dairying regularly brought significant profits to the farms. The meat cattle farming also had remarkable results – Kuffner pork ham was known for its quality for the Christian part of society, and kosher bulls (they were not allowed to be castrated) were equally in demand and went as far as Vienna to Jewish families there. Good organising skills and the use of all the products in the farmyards without remnants, i.e. the waste part of the sugar beet, the cultivation of their own fodder and other cattle feedstuffs, led the Kuffner estate to complete independence and autonomy and at the beginning of the 20th century it became one of the most progressive farms in southern Moravia. In 1924, the Hodonín Akciová společnost pro průmysl cukrovarnický (Joint Stock Company for the Sugar Industry) bought all the shares in Kuffner’s Břeclav sugar factory as it sought to acquire as many sugar factories in Moravia as possible. However, already in the first years after the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic, all the farmsteads on which Kuffner’s Břeclav sugar factory had been operated were seized by the State Land Office as part of the land reform and either parcelled out or made into residual estates. In 1924 Karl Kuffner also died and his only son Raoul did not devote himself fully to the family business; from the 1930s he lived outside Slovakia and with the onset of fascism he sold the company and moved to the United States.

Jewish Ceremonial Hall in Břeclav

The present-day landmark of the Jewish burial grounds, the neo-Gothic ceremonial hall from 1892, had a turbulent fate. In that year, the cemetery area was expanded. The land was donated by brothers Hermann and Jacob Kuffner, and Moritz Kuffner became the financial donor of the entire refurbishment project. The prominent Austrian architect and politician Franz Knight von Neumann Jr. (1844–1905), who came from a famous Viennese family, was invited to create the design. His most famous works in this country include the Neo-Renaissance town halls in North Bohemia (Liberec and Frýdlant); those that have not been preserved include a tower on Mt. Praděd (which collapsed in 1959). Of course, Neumann also left an indelible trace in his native Vienna (the arcaded houses on the square of Radniční náměstí or the Habsburg lookout tower on the hill of Hermanův vrch), where he worked, among others, in the service of the Viennese branch of the Jewish Kuffner family. Neumann was the author of the now beautifully restored Kuffner Observatory in Ottakring from 1890, the first private observatory in the Habsburg monarchy, and the sumptuous Kuffner Villa and city palaces. The Ceremonial Hall is a ground-floor hall building with a double-pitched roof and a gable. Inside, the visitor is impressed by the pseudo-Gothic (false) ribbed vault with historicising paintwork. The walls have German and Hebrew inscriptions. After the war, the building was used as an upholstery and drugstore warehouse and its deplorable condition necessitated at least a basic repair of the roof in the 1990s. The former undertaker’s house was also repaired at this time, including an extension for residential purposes. In the years following World War II, a neighbourhood of houses gradually grew up near the cemetery and there were increasing calls for the old “useless” burial ground to be disposed of. Eventually, the highly neglected area of the Jewish cemetery was terminated in the 1980s by the decision of the then city and county officials – the more recent southwestern part was closed and the tombstones were removed. After the change of political situation, the town authority of Břeclav had the area landscaped in 1991–1993 and all the old tombstones were repaired and reinstalled in the area of the ravine. The INTERREG V-A Slovakia – Czech Republic 2014–2020 grant enabled, as part of the project entitled In Eternal Memory, the Kuffner family in Moravia and Slovakia, the generous restoration of this cultural monument in 2023. Owned by the town of Břeclav, the building will be used for cultural and social purposes

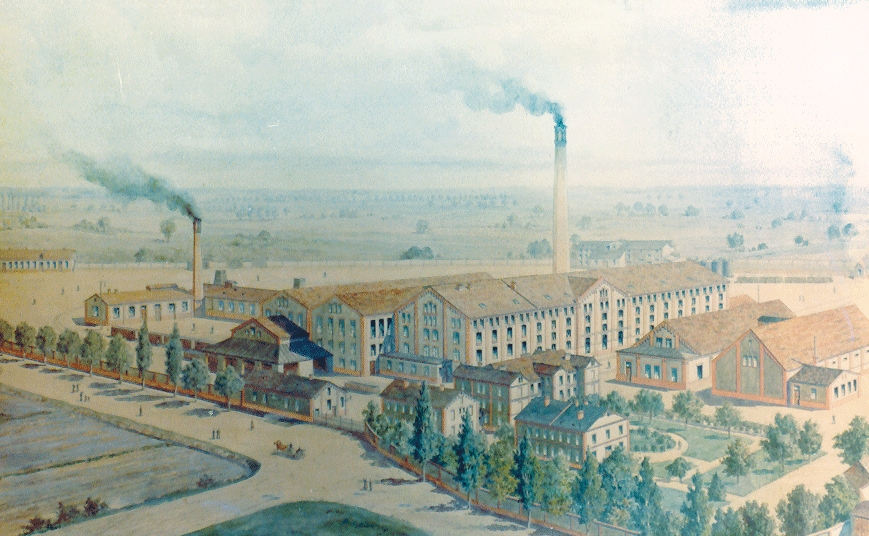

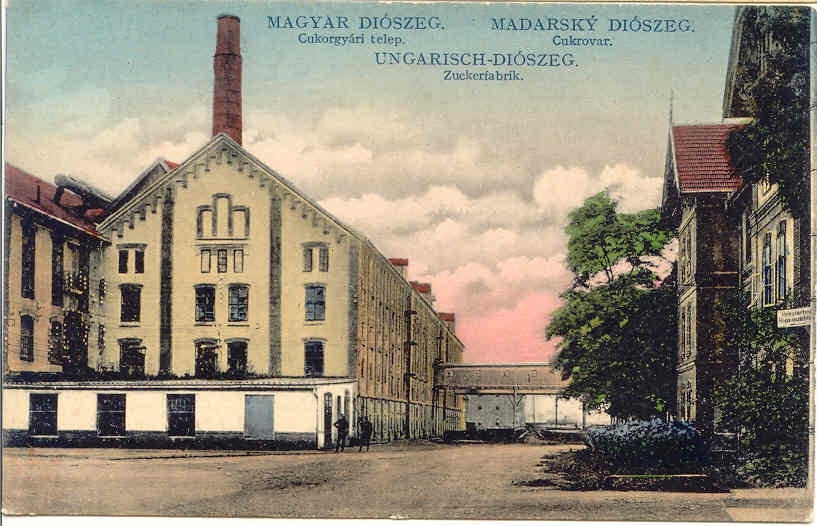

Sugar Factory in Sládkovičovo

The surroundings of the former Upper Hungarian town of Dioszegh, with a population of less than 2,000 Hungarian and German inhabitants, offered favourable conditions – climate, abundant water and direct railway services to Budapest and, via Bratislava, to Vienna – for growing sugar beet. Jacob Kuffner, together with his brother Hermann, his cousin Ignaz and members of the Viennese wholesaler Gutmann family, bought 20 morgens of land from Count Zichy (the Hungarian morgen was equal to about 43 acres) and built a factory. The modern sugar factory processed 96,240 q of sugar beet as early as in the first harvest period (lasting 160 days) in 1868 and produced 72,910 q of sugar. The excellent economic results (more than 26 thousand guldens) and the boom in sugar sales meant that the company soon bought 1,010 morgens of land for growing sugar beet. As in Břeclav, the surpluses from sugar production, such as molasses, were used in the newly built distillery. The sugar refinery was registered as a private company under the name DIOSEGHER ZUCKER-FABRIK VON KUFFNER & GUTMANN WIEN with its registered office in Vienna. After extensive renovation and upgrading, the sugar factory was transformed into a joint-stock company in 1873 with a share capital of 1,500,000 guldens, and a quarter of a century later the headquarters were moved from Vienna to Dioszegh. By this time, Karl Kuffner, the younger son of Jacob, was already clearly the leading figure in the dynamically developing economy who in the years before World War I turned the Dioszegh factory into one of the most important sugar factories not only the Habsburg Monarchy but in the whole of Central Europe. Karl Kuffner (1847–1924) was a great advocate of intensive production in agriculture and the food industry and became one of the pioneers of the introduction of the most modern methods and technical inventions into business. He personally patented several ideas for improving sugar beet processing technology. His sugar refinery and its accompanying farms were becoming a model modern enterprise equipped with telephone lines, a narrow-gauge railway for the transport of sugar beet and other technical conveniences. Under his leadership, a private agricultural research institute for crop and livestock production was set up in Dioszegh. At this institute, the plant specialists concentrated on the breeding of sugar beet, wheat and maize (the new wheat species called Dioszegh Goliath gained the most attention), while in the livestock sector, the Dioszegh method of breeding and fattening cattle was known very well and used throughout Hungary. In 1896 Karl Kuffner was elevated to the noble status with the predicate de Dioszegh for his life’s work and merits. Eight years later, he received the rank of Baron of Hungary (with the right to use the title for the whole family). His only son, Raoul (1886–1961), no longer devoted himself to the family business, resided outside Slovakia from the 1930s onwards, and with the onset of fascism sold the company and moved to the United States.

Ottakringer Brewery in Vienna

The brewery’s history begins with master miller Heinrich Plank of Rannersdorf. In 1837 he obtained a brewing licence and the right to establish a brewery in the Viennese suburb of Ottakring (now the 16th district of Vienna). In 1850 the brewery was bought from the indebted Plank by cousins Ignaz and Jacob Kuffner. This launched the almost 90-year successful history of the company associated with this Jewish family, which did not end before the Arisierung of their property in 1938. In 1856, the cousins bought another brewery in Ober-Döbling (now Döbling, 19th district of Vienna). This brewery would become the main focus of Jacob Kuffner’s work, and under his leadership, it became no less prosperous. Ignaz Kuffner (1822–1882) soon expanded the brewery to a large-scale production format and, in addition to beer, also produced spirits and pressed yeast on the premises. He transformed the Ottakringer Brewery into a model company by raising the technological level, multiplying production and introducing exemplary labour and social regulations (an in-house kitchen for workers, etc.). It was for his work in the brewing industry and his humanitarian services that he was elevated to the noble status of Edler von Kuffner in 1878. After he died in 1882, the company was taken over by his only son Moritz Kuffner (1854–1939). During the era of this important personality of Vienna’s economic, social and philanthropic life, the brewery became one of Austria’s most prosperous businesses. After the unexpected death of his eldest son Ignatz (born 1892) in early 1938, the younger son Stefan (1894–1976) took over the management of the Ottakringer brewery, albeit briefly. Just one day after the Austrian Anschluss, on 13 March, SA troops attempted to occupy the brewery as a purely Jewish property. The Kuffners therefore appointed their “Aryan” co-worker Dr. Karl Schneider, who had long been in charge of the brewery's chemical laboratory. Soon, given the worsening situation, they sold the brewery for 14 million shillings to Gustav Harmer, a distiller from Spillern near Stockerau. This prevented the confiscation of the business and provided the means to live in emigration. Today, the brewery produces 20 different beers and has an annual output of more than 540,000 hectolitres. As of 2018, it is housed in new premises and is focused on greening and environmental sustainability. Tours of the premises and events organised by the brewery are among the most visited attractions in Vienna.

Kuffner Observatory in Vienna

The most enduring legacy of Moritz Kuffner (1854–1939) to the city of Vienna involves the still-existing Kuffner Observatory, the first private observatory in the Monarchy. From the beginning, it was run by eminent scientists and several times held the world’s top position in astronomical observatory equipment. The design of the observatory building was in the hands of the architect Franz von Neumann Jr. This famous Viennese architect was influenced in the planning of the observatory by the university observatory established ten years earlier. In addition to the brick structure, often used in historicist buildings, it also adopted a cross-shaped plan that allowed for a favourable combination of residential and administrative wings with a centrally located observatory. The observatory consists of a main building with a refractor dome. The foundation stone was laid in the summer of 1884 and the building was completed in early 1887. In 1892, Moritz Kuffner decided to build a flat for the second assistant in the north wing of the building and also a villa for the director located about 100 metres east of the observatory. The built-up area of the observatory with the outbuildings totalled around 1,150 square metres; the cost of construction was around 170,000 guldens. The large park to the north and east and the small annex building for measuring the meridians, the Mirenhaus, which stood to the left of the entrance to the garden, parts of the original Kuffner Observatory, no longer exist. The most important scientific figures associated with the Kuffner Observatory include Samuel Oppenheim (1857– 1928), Karl Schwarzschild (1873–1916) and Gustav Eberhard (1867–1940). In 1987 the observatory was purchased by the city of Vienna and between 1989 and 1995 the entire grounds were extensively renovated and enlarged. In 1993, a project was launched to restore the astronomical instruments to their exact form. Today, the 19th-century Kuffner Observatory, a listed building, impressively shows how astronomical research operated more than 125 years ago. Thanks to the good condition of the historic instruments, it is still possible to observe the night sky today as it was then. The faithfully restored astronomical instruments and the atmosphere of the historic building both offer visitors an extraordinary experience.

.JPG)